Shingo Research and Professional Publication Award recipient

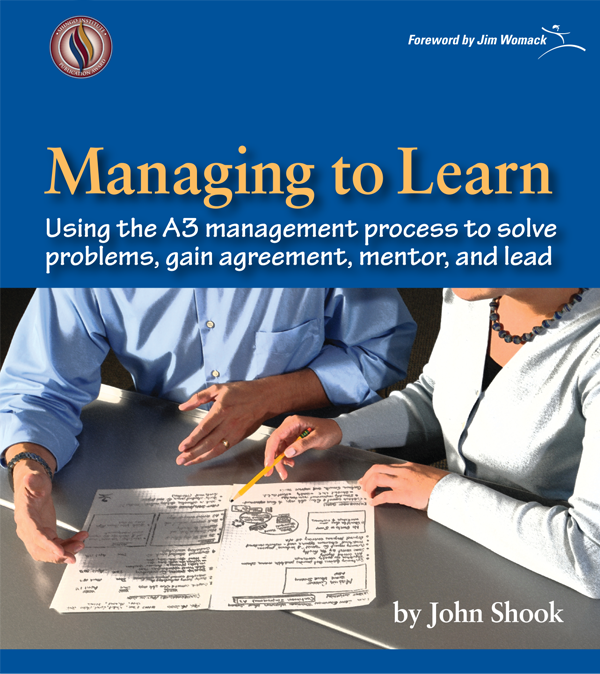

Managing to Learn by Toyota veteran John Shook, reveals the thinking underlying the A3 management process found at the heart of lean management and leadership. Constructed as a dialogue between a manager and his boss, the book explains how “A3 thinking” helps managers and executives identify, frame, and act on problems and challenges. Shook calls this A3 approach, “the key to Toyota’s entire system of developing talent and continually deepening its knowledge and capabilities.”

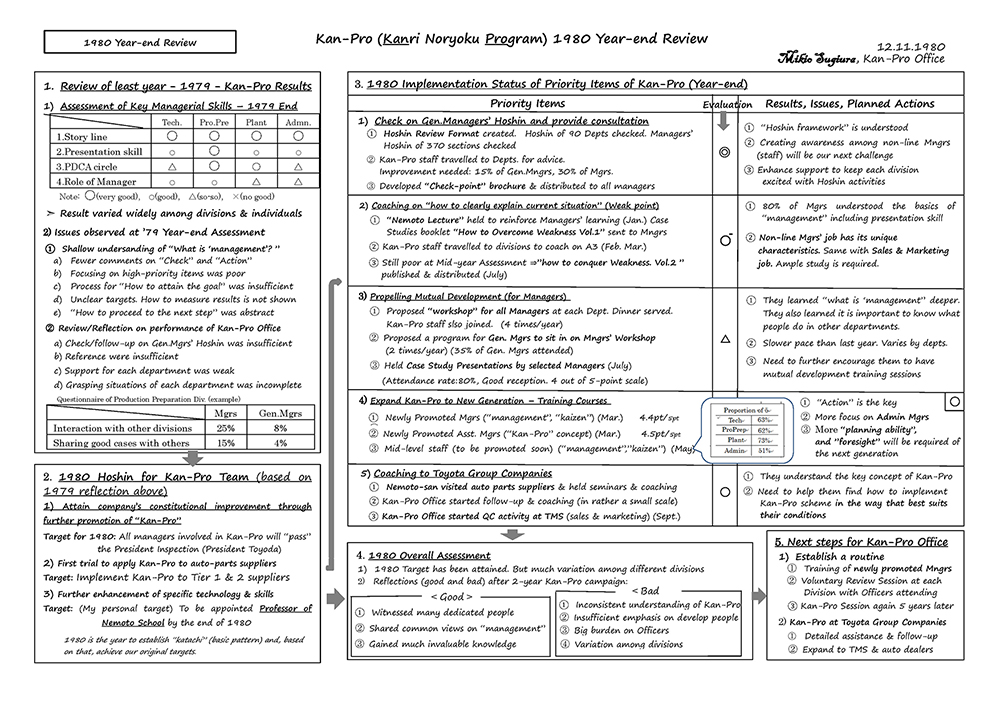

The A3 report is a Toyota-pioneered practice of getting a problem, its analysis, the corrective actions, and action plan down on a single sheet of large A3 paper. (A3 paper is the international term for a large sheet of paper, roughly equivalent to the 11-by-17-inch tabloid sheet.)

“The A3 process standardizes a methodology for innovating, planning, problem-solving, and building foundational structures for sharing a broader and deeper form of thinking that produces organizational learning deeply rooted in the work itself,” says Shook.

A unique book layout puts the thoughts of a lean manager struggling to apply the A3 process to a key project on one side of the page and the probing questions of the boss who is coaching him through the process on the other side. As a result, readers learn how to write a powerful A3—while learning why the technique is at the core of lean management and lean leadership.

Who Benefits

Executives and managers at all levels in the organization will benefit from the book. An A3 can be used wherever there is a need for people to work together to get clarity on a problem or proposal and then to create a set of realistic and effective countermeasures. A3s can be prepared by individuals, teams, or any leader and his or her report.

Chapter Downloads:

Readers will learn an underlying way of thinking that reframes all activities as learning activities at every level of the organization, whether it’s standardized work and kaizen at the individual level, system kaizen at the managerial level, or fundamental strategic decisions at the corporate level.

–Jim Womack, Founder and Senior Advisor of LEI

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.