Books

A3 Getting Started Guide

Although this guide isn’t the end-all-be-all for how to use the A3 process, it includes some of our favorite tools,…

Price

$12.99

Price

$12.99

Managing to Learn: Using the A3 management process

Managing to Learn by Toyota veteran John Shook, reveals the thinking underlying the A3 management process found at the heart…

Price

$50.00

Price

$50.00

Learning to See

Value-stream maps are the blueprints for lean transformations and Learning to See is an easy-to-read, step-by-step instruction manual that teaches…

Price

$60.00

Price

$60.00

Becoming the Change

Two renowned healthcare transformation experts provide a blueprint for implementing the principles and behaviors leaders at all levels must embrace…

Price

$32.00

Price

$32.00

Building a Lean Fulfillment Stream

This workbook explains step-by-step a comprehensive, real-life implementation process for optimizing your entire fulfillment stream from raw materials to customers,…

Price

$60.00

Price

$60.00

Creating Continuous Flow

This workbook explains in simple, step-by-step terms how to introduce and sustain lean flows of material and information in pacemaker…

Price

$60.00

Price

$60.00

Creating Lean Dealers

Car manufacturing has been transformed by Lean over the last 20 years yet car dealerships have remained virtually untouched by…

Price

$65.00

Price

$65.00

Creating Level Pull

Creating Level Pull shows you how to advance a lean manufacturing transformation from a focus on isolated improvements to improving…

Price

$60.00

Price

$60.00

Creating Continuous Flow / Making Materials Flow Set

Buy the two workbooks on flow together and save 15%. Continuous flow cells need a lean material-handling system to supply…

Price

Original price was: $120.00.$102.00Current price is: $102.00.

Price

Original price was: $120.00.$102.00Current price is: $102.00.

Designing the Future

Today’s elite companies know that the ability to consistently create successful new products and services is their most powerful competitive…

Price

$24.00

Price

$24.00

Designing the Future/Lean Product & Process Development, 2 edition book set

Price

Original price was: $94.00.$80.00Current price is: $80.00.

Price

Original price was: $94.00.$80.00Current price is: $80.00.

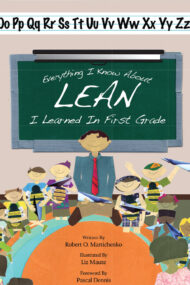

Everything I Know About Lean I Learned in First Grade

Everything I Know About Lean I Learned in First Grade is a quick, fun introduction to lean principles. The book…

Price

$20.00

Price

$20.00