Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on January 15, 2021. It is the first of three focused on the importance of people development in creating and sustaining a lean enterprise. The series explores the theme through three critical dimensions: leadership, coaching, and training. This inaugural piece delves into leadership.

In this video, Art Smalley sheds light on the dynamic concept of situational leadership, offering crucial lessons on how to assess a team member’s needs and adapt leadership styles to support the team member most effectively.

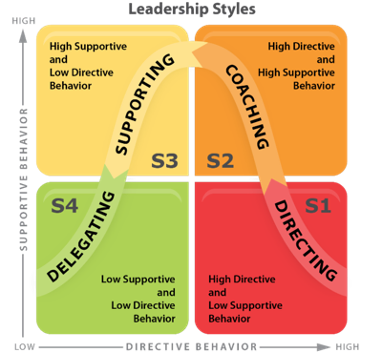

Based on foundational research by Paul Hersey, Ken Blanchard, and Dewey Johnson, Smalley discusses how effective leadership must evolve to elevate individuals to their highest potential, an idea central to lean thinking.

Key takeaways include understanding four developmental levels and their corresponding leadership styles illustrated in the following graphic:

Join us at the 2024 Lean Summit on March 19-20, where “Shaping Tomorrow, Developing People” will be our central theme. Connect with and learn from lean leaders on the pivotal role of people development in building a lean enterprise.

This video is the first in a five-part series by Art Smalley on situational leadership. Access the remaining videos here: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5.

Key Concepts of Lean Management

Get a proper introduction to lean management.