This article was first published on MIT Sloan Management Review Brazil (https://mitsloanreview.com.br/yokoten-capturando-e-disseminando-boas-praticas/)

Henry Ford was a pioneer in developing the assembly line for cars, a revolutionary concept that transformed the automotive industry. Surprisingly, Ford drew inspiration from an unexpected source: the “disassembly line” used in cattle slaughterhouses in Chicago.

Following his enormous success, he directly enabled widespread knowledge transfer by building a small assembly operation at an industrial exhibition in San Francisco to showcase his practices, just a few years after installing his groundbreaking assembly line in Highland Park, Michigan.

A few years after its creation, Ford’s assembly line became the standard for assembly operations, not just in automobile manufacturing but across various industries.

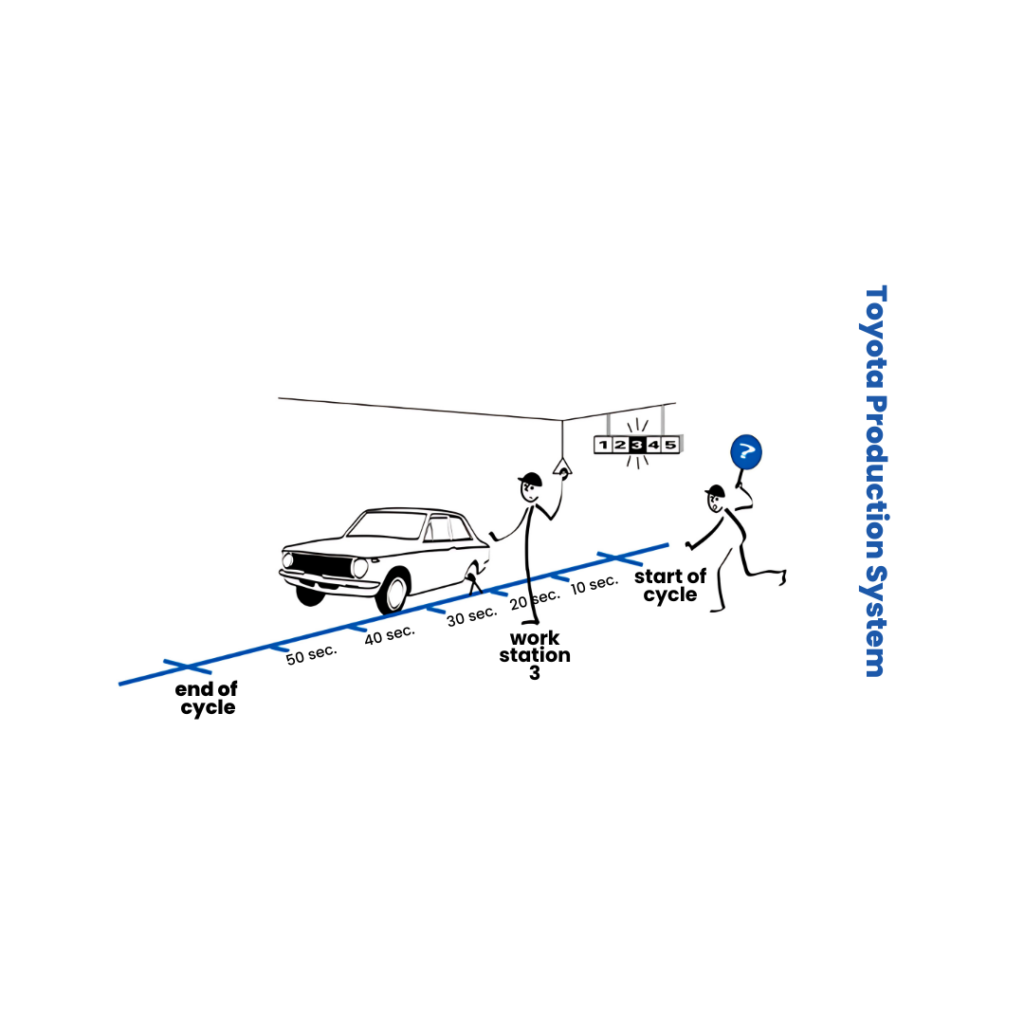

One company that benefited from the flow conceived by Ford was Toyota. When it sought to close the productivity gap with American carmakers in the 1950s and 1960s, Toyota realized it needed to make significant improvements. The company also looked at how supermarkets operated in the US. Based on those observations, Toyota created the just-in-time concept, which, combined with numerous other experiments, led to the development of the Toyota Production System (TPS).

As we engage with various management and work practices, we inevitably encounter new concepts and methods we can apply to our own realities. These ideas, already tested, proven, or learned by others in different situations, can help us solve our own problems by expanding our repertoire of responses. They can also inspire us to leap forward in innovation.

Sharing and reusing knowledge is invaluable when someone discovers a more effective way to carry out a task or process and incorporates it into their work standards. This process is known as “yokoten”.

Yokoten and Its Benefits

Yokoten aims to share and reuse knowledge, concepts, policies, and best practices. It can be translated as “horizontal expansion,” where yoko means “horizontal” and tenkai means “unfolding” or “development.”

We should consider both explicit knowledge, which is visible and easy to articulate and share, and tacit knowledge, which is often less visible and harder to identify, formalize, and transfer.

Toyota has made extensive use of yokoten, which played a key role in its transformation into a global company by expanding and adapting its learning practices and values across multiple units and operations.

Companies in many sectors have followed this learning path. Factories, hotels, banks, healthcare, agriculture, software, construction, and more have adopted good practices developed in other contexts, learning from others.

Figure 1: Yokoten: horizontally transferring best practices

Yokoten serves as an antidote to typical hierarchical approaches where companies define “best practices” from corporate offices far away from the gemba and impose them across all areas. The focus in such cases is on compliance and centralized control, often enforced through audits. There is little encouragement for learning, experimentation, or continuous improvement.

For any organization aiming to stay competitive and avoid stagnation, it’s essential to cultivate a well-defined learning strategy that serves as a powerful catalyst for continuous improvement.

Yokoten offers several advantages, such as saving time by implementing solutions already tested elsewhere. It also facilitates organizational learning from better approaches to similar problems, accelerating the learning curve and enhancing operational outcomes.

Moreover, it can serve as a valuable tool for revitalizing companies struggling with continuous improvement strategies.

Executing Yokoten

Yokoten can occur organically at any time, in any place, as an informal process driven by open-minded individuals willing to learn and aware of what’s happening around them.

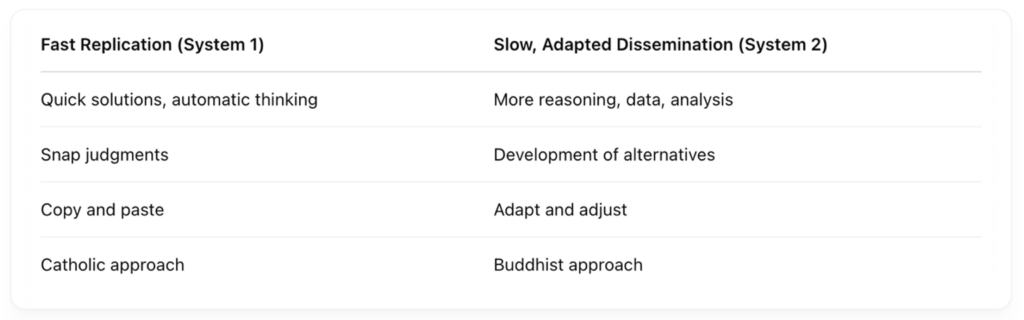

Alternatively, it can be implemented intentionally and systematically, as we suggest here. Sutton and Rao propose two primary approaches to spreading good practices (“excellence”):

a) The “Catholic” approach: creating perfect replicas that mirror the original practices and standardizing them.

b) The “Buddhist” approach: encouraging local variation, experimentation, and customization to meet specific needs.

Both approaches can be used depending on the process and environment. A purely “Catholic” approach can work if teams are mature, and the focus is well-defined. However, merely replicating practices may lead to missed learning opportunities. There should always be room to improve the new practice, as the implementing team might offer valuable suggestions.

A purely “Buddhist” approach, on the other hand, may result in excessive variation, limiting standardization and stabilization efforts, and making continuous improvement harder to sustain.

We can define two phases in the yokoten process:

a) Identifying and capturing good practices based on specific needs and purposes.

b) Replicating them in target areas.

A) Identifying Good Practices

Many organizations contain isolated pockets of effective practices. However, we often rely on vague evidence, impressions, or intuition to assess them properly. Even when quantitative data is available, the link between practices and results might not be immediately obvious.

It’s important to ask whether the person leading the yokoten process is truly prepared to observe good practices with the necessary critical sense. Learning by doing is the main way to develop this capability, and over time, practice will help individuals recognize their own limitations.

Defining the need and purpose of the yokoten process should lead to a clear scope and proper selection of the practices to observe and adopt – establishing a focused learning plan.

Going to the gemba (the place where the work happens) is crucial for identifying good practices. While visiting the gemba, certain behaviours are recommended: respect the individuals involved – they are setting aside their own tasks to help you. Approach each interaction with humility and genuine curiosity. Be mindful of how and where you ask questions – avoid rhetorical, abstract, embarrassing, or confrontational ones.

Discovering these successful practices requires engaging all your senses: sharp eyes for keen observations, open ears for active listening, your voice to ask insightful questions, physical mobility to get close to the actual work, and a strong method for documenting and capturing learning – alongside appropriate metrics to assess effectiveness.

While at the gemba, you may randomly discover valuable practices that can be applied to your own work context, helping to solve problems and drive improvement, providing additional learning.

Yokoten can be seen as a form of personal training or a practical, customized “MBA” tailored to specific needs. Imagine accessing experienced professionals with a deep understanding of challenges similar to yours – offering real, actionable advice instead of abstract concepts.

To make the most of this learning opportunity, show up ready and willing to fully engage. Be focused and prepared to observe attentively and understand. Take detailed notes, photos, videos, etc., whenever possible. Ideally, direct your attention toward model areas or reference areas that clearly demonstrate what good practices look like – with advancements not just in tools and methods, but also in behaviours and attitudes.

Sometimes, these model areas arise naturally due to leadership maturity, business conditions, or a crisis that spurs innovation. In other cases, yokoten is the result of intentional and structured efforts.

Each practice brings not only a specific way of doing the work but also a way of thinking – often less visible. Observing without understanding the invisible or hidden elements of those practices weakens the learning.

Success in identifying practices depends on leadership maturity and people’s ability to make proper observations. Either way, it helps develop leadership skills.

B) Disseminating Good practices

Once the observation phase is complete and relevant practices have been captured, the next step is to transfer them to your own area. The real value of yokoten is only realized when those practices are effectively implemented in context and deliver tangible results.

Whether a fast replication or a slower, more deliberate adaptation, whether simple or complex, implementation demands careful, thoughtful planning to ensure success.

This challenge is well illustrated by one of the most commonly observed – and copied – TPS practices: the activation of the help chain via the “andon,” where any worker can stop a process or production line by pulling a cord (or pushing a button) when they face a problem they cannot resolve in a preset time. Introduced by Toyota as part of the “jidoka” pillar, this practice ensures quality by summoning leadership to assist in solving problems using predefined criteria.

Many companies recognized the value of this practice for quality assurance and implemented andon systems at various workstations, assuming implementation would be straightforward. However, many of these implementations – which were considered to be “Catholic” approaches that aimed to rapidly “copy and paste” the practice – turned out to be shallow and unsustainable over time. Few companies managed to maintain the practice effectively.

Why is this so challenging? Technically, there may be a lack of standardized work and clear guidelines on when and whom to ask for help. Social factors also play a major role: low trust in front-line workers, unclear leadership roles, and poorly structured help chains.

Real Examples

We can illustrate yokoten with real-life examples to highlight how the nature of the activity can affect the dissemination process. Let’s look at two cases: (a) a critical stage in a logistics process that involves physical work, using the “shadow loading” method; and (b) intellectual work involving integration between teams from different functional areas, through the practice of “daily management.”

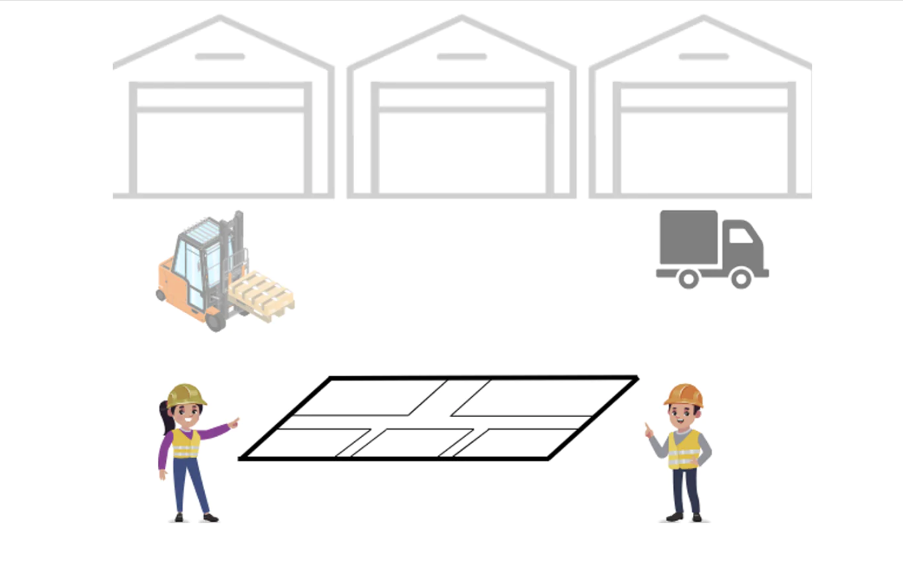

Shadow loading (illustrated in the figure below) is a process used to load a truck. It consists of a layout marked on the floor, next to where the truck will actually be loaded, that replicates the space each item will occupy in the truck.

This practice can be observed at the gemba and may seem simple enough to be quickly “copied and pasted” as a fast replication. In this case, it might appear sufficient to share a photo with the implementation team, explain the purpose and benefits, and proceed with the rollout.

Once the implementation is planned, the floor is marked, and warehouse workers can begin positioning the real materials in their designated pallet spaces on the ground – prior to the truck’s arrival. This practice reduces truck wait times, speeds up the loading process, and decreases the likelihood of errors and rework.

Although simple and logical – allowing teams to work more efficiently, safely, and intelligently with easy-to-follow visual standards – there are often underlying complexities to consider. For example: Does the team believe this change is beneficial? Have they “bought in”? Do they see it as an improvement over the current practices? Furthermore, how do you ensure stability, standardization, and continuous improvement of these practices? Without addressing these questions, what initially seems like a good practice may not be implemented or sustained effectively.

Another example is the effort to foster teamwork between distinct functional areas, such as sales and operations. You might be impressed when visiting a model site where this practice is well established, for example, in the daily “daily management” meetings. However, transferring it to another site may not be so straightforward.

Successful collaboration requires several steps. These may include setting a strategic direction that aligns both areas with shared objectives and goals, practicing teamwork on a daily basis, and establishing key cultural elements that create an environment of trust and cooperation – avoiding the trap of departmental silos.

In any case, transferring new practices will always require some reflection and careful planning to address existing cultural assumptions and ensure success.

Observable practices (explicit knowledge) are often supported by deeper and more subtle layers of beliefs, behaviors, and assumptions (tacit knowledge), which are significantly harder to identify and transfer.

Thus, yokoten involves more than simply “copying and pasting”; it requires a deep understanding of the underlying beliefs and assumptions, and adaptation to the specific context and needs. A quick-fix approach is often insufficient.

Defining the speed and scope of implementation – whether to move quickly or slowly, broadly or with focus – is a critical decision. These decisions depend on the nature of the process, the associated risks and uncertainties, and the maturity and knowledge level of the involved teams, especially the leadership.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman illustrates how our brain works and how decision-making is influenced by two distinct thinking systems: System 1 operates quickly, allowing individuals and organizations to make judgments and act based primarily on intuition and automatic thinking. This often leads to hasty conclusions or premature solutions. System 2, on the other hand, requires more deliberate reasoning, considering data, awareness, and careful processing.

System 1 often prevails because people believe they already know the answer, or because the situation feels familiar, and the problems seem simple enough not to require deep consideration.

Based on this, we can adopt two main approaches to yokoten:

The dissemination process may initially progress slowly, as it calls for a deep understanding of the practices, the problems to be solved, and the underlying beliefs and assumptions. However, the pace can increase when individuals share aligned purposes, mindsets, and beliefs.

As a company continues to achieve consecutive successes, senior leaders often try to accelerate the yokoten process – especially when the early gains are visible.

Planning for Action

To carry out yokoten successfully, it’s essential to develop an action plan. Start by identifying the problems that need to be solved, decide on the practices you intend to adopt in your organization, and clearly describe the steps required to implement these new practices. Make sure the yokoten action plan is aligned and prioritized in coordination with other existing plans – both strategic deployment plans and knowledge management or reuse initiatives.

Some helpful questions to ask include:

- What specific problems are you trying to solve?

- Which best practices will you seek out and capture?

- How will you implement these practices?

- When will these changes take place?

- Who will be responsible for implementation?

- What potential obstacles and risks must be considered?

The pace and method of implementation can depend on several factors:

- Leadership capability, motivation, and commitment: The skills and enthusiasm of leaders significantly influence how quickly and effectively new practices are adopted.

- Clarity of purpose and problem: A solid understanding of the specific problems to be addressed and the objective of the practice ensures a focused implementation.

- Expected benefits: Assessing why the new practice is valuable helps gain team buy-in.

- Team alignment: Forming a small, dedicated team that understands and supports the new practice helps deepen knowledge and engagement.

- Risk assessment: Anticipating potential challenges and preparing for them helps mitigate risks.

- Knowledge and skill development: Building team capabilities and encouraging learning by doing are essential for sustainable success.

- Cultural fit: Identifying core assumptions and values that might conflict with the proposed practice is key to long-term adoption.

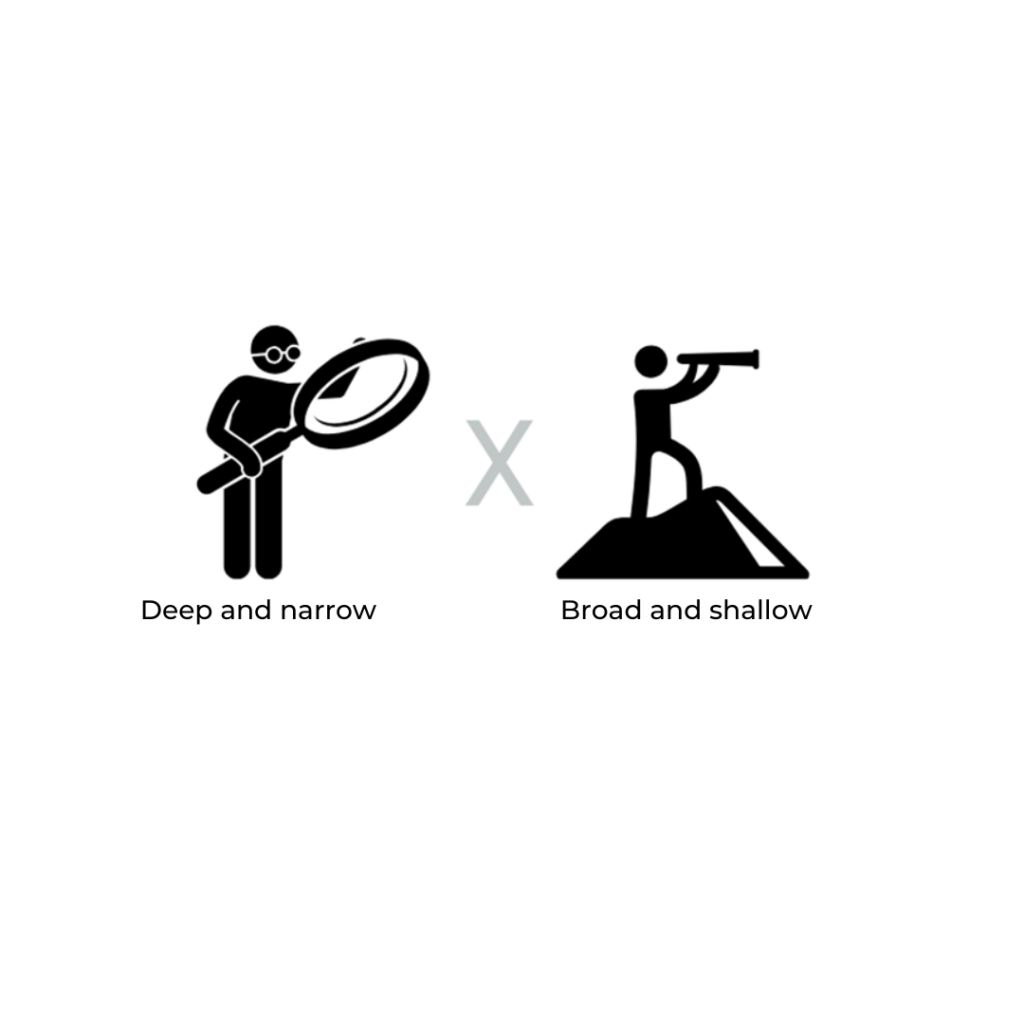

Choosing the appropriate scope is another crucial decision. You can opt for a “deep and narrow” approach or a “broad and shallow” one.

The first focuses the initiative on limited areas to enable rapid learning and greater attention to detail, allowing closer control over variables. This approach empowers people and leads to more sustainable results, although expansion may take longer.

The second allows for faster implementation across a wider scope but tends to face greater difficulties with engagement, sustainability, and learning.

Both approaches have their strengths and weaknesses and can be used at different stages of implementation. For initial learning, the “deep and narrow” approach is often more effective.

Starting with small, focused efforts helps involve the individuals who need to understand and support the changes, while also allowing obstacles to be addressed early.

Designing Replication Experiments

As part of the action plan, it may be helpful to propose replication experiments during the dissemination process to learn and assess whether adjustments are needed. Reflecting on the earlier example of challenges in replicating the “andon” technique, many companies hired consultants for broad-scale implementation – but often only achieved superficial results. Some even went so far as to build new assembly plants to implement this and other practices. Unfortunately, the outcomes have frequently been questionable, with the new practices failing to sustain over time.

A more successful strategy might have taken a different approach. Companies could have started with a small experimental pilot – testing, learning, adjusting, and only then expanding. Running experiments is invaluable, as it offers a structured way to learn by testing hypotheses. Even if it feels like “reinventing the wheel” instead of simply applying something already proven, this method can yield deeper and more sustainable results.

After these experiments, teams can begin implementing Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycles to effectively carry out the replication strategy.

Plan

- Identify the areas from which you want to learn and the problems you want to solve.

- Define the new practice you intend to learn and replicate.

- Select a leader for the implementation team.

- Ask the leader to form a small, focused team.

- Together, define the scope of the experiment and the evaluation metrics.

- Develop an action plan including a timeline, management system, expected deliverables, and a transition plan if needed.

- Document these elements in a concise one-page plan.

Do

- Implement the practice using a visual management approach, such as a board or an “obeya” (war room), integrated into daily management whenever possible.

- Display the one-page plan on the board, showing ongoing actions, achieved results, and lessons learned – positioned near the gemba.

Check

Reflect on the key learnings and challenges.

Review the actions taken and the initial results.

Act

Conduct a reflection session with the team (hansei) after implementation to capture the learnings and standardize the new practice. Follow-up can vary from weekly to daily, depending on the situation.

Ultimately, your knowledge, specific needs, and your team’s capabilities and willingness will determine the pace and scope of your efforts.

Approaches to Yokoten

As noted earlier, there are many approaches and methods for carrying out yokoten. In many large corporations, knowledge sharing and mutual learning between different areas or units can be greatly enhanced by establishing and maintaining a systematic and recurring process.

In an organization that operates across multiple processes and locations, there are several opportunities to implement yokoten, such as:

Internal Yokoten:

- Intradepartmental: within the same functional area.

- Interdepartmental (intra-site): between different areas within the same location.

- Inter-site: between different geographic units.

- Inter-organizational: between different business units within the same company.

External Yokoten:

- Cross-industry: learning from other companies in the same sector or in related industries.

- Cross-sector: learning from a wide range of external sources, regardless of industry.

The types of observation and learning activities can also vary, such as:

- Immersion: involves deep observation and participation in meetings, direct interaction with people, and interviews at the gemba. This process can take several days.

- Visits: typically consist of more surface-level observations during gemba walks. These usually last a few hours.

- Best practice presentations: focused on sharing good practices, these sessions may last a few hours and can be combined with gemba visits.

- Industry events, meetups, or conferences: these can provide opportunities to observe and learn about shared practices.

- Staff exchange: involves rotating or exchanging individuals and teams through visits or temporary assignments. These exchanges can last several weeks.

Can Dissemination Be Accelerated?

How fast can we move forward? The speed of implementation depends on your capabilities and your team’s readiness to embrace change and learn. Each new practice presents an opportunity for growth and the need to develop both your team’s skills and leadership capabilities. People will learn as they capture successful practices and spread them.

However, inaction implies complacency, suggesting that you and your team are stuck in your comfort zones, focused solely on maintaining current performance levels. This mindset can lead to stagnation and a gradual decline in results.

Trying to progress too quickly along the learning curve – faster than your actual capabilities – can result in superficial, and often unsustainable, implementation.

James Womack discusses the pace of idea and innovation dissemination using two examples from surgical history:

(1) the spread of anaesthesia using ether, and

(2) the use of disinfectants on instruments and surgeons’ hands.

While the first spread almost instantly around the world, the second took many years to gain traction.

The reasons for this difference lie in how quickly the benefits of anaesthesia were visible to patients – without complicating surgeons’ work – while disinfecting instruments required major changes to routines: thorough cleaning of gloves and tools, handwashing, and slower procedures. These slowed down surgeries, reduced productivity, and the benefits weren’t immediately visible – unlike with anaesthesia.

The parallels with a lean transformation are striking. Easier and faster changes typically involve practices that don’t disrupt routines or structures, require little new knowledge, can be implemented by specialists while managers observe, and produce quick, measurable results – such as continuous flow, 5S, visual management, etc.

By contrast, the spread of ideas becomes slower and more difficult when it demands deeper knowledge, structural and organizational change, or must be led by managers themselves. Changing leadership style and management systems is slow, as it requires challenging the fundamentals of managerial thinking – shifting from command and control to coaching and mentoring.

Ironically, the most transformative, impactful, and lasting results come from the changes that are hardest to implement and slowest to measure.

Well-designed and focused replication experiments will yield the learnings and outcomes needed to motivate and engage your team. This approach ensures the right balance of speed, quality, and continuous learning that drives operational improvement.

Yokoten must play a key role in any organization’s improvement strategy. It accelerates the learning curve, intensifies knowledge reuse, and expands the range of practical solutions.

But this process must be far removed from “industrial tourism” – where people wander through different sites seeking inspiration or admiring “best practices” – and from benchmarking processes that focus mostly on comparing metrics, often without understanding the drivers behind superior performance.

In this article, I suggest yokoten as a deliberate and effective way to “learn from others” while avoiding superficial “copy and paste” solutions that are often disconnected from specific contexts and cultural assumptions – and therefore, unsustainable over time.

New knowledge can come from many internal or external sources. But having a model area to begin with is extremely helpful for generating deeper learning.

A clear purpose for yokoten should guide both your action plan and learning focus, always aligned with your organization’s business needs.

A good plan for implementing observed best practices must go beyond visible tools and include tacit knowledge. Running experiments is an excellent path to generating deep learning.

Quick replication may eventually happen, but some adjustments and adaptations are usually needed.

Through yokoten, learning will grow exponentially – which is vital in times of rapid change in markets, competition, and technology. This may be the key to amplifying transformation processes while saving time, resources, and effort.

This article is based on the author’s decades of experience helping companies learn from one another. It all began in the 1990s, when the impact of the book The Machine That Changed the World inspired many automotive companies to copy Toyota. In the decades that followed, businesses in various industries have tried to follow this path. The author would like to thank Rune Thorstensen, José Renato, and Fabio Vilabela, as well as the leadership team at TechnipFMC Serviços (in the energy sector), for the many yokoten opportunities in their operations. Special thanks also go to Luciana Gomes, Flávio Battaglia, and Daniel Felipe de Oliveira for their feedback and suggestions on this text.