In my experience, too many lean practitioners still approach the A3 report merely as a template with several boxes to fill in. Whenever I come across this, I try to help people see how limiting — and wrong — this view is. Instead, as my Japanese coaches taught me, an A3 report is a tool that encourages a systematic way of thinking through and addressing problems. Indeed, they showed me that the A3 process, based upon the plan, do, check, adjust (PDCA) improvement cycle, is designed as a way to “share wisdom” with the rest of the organization.

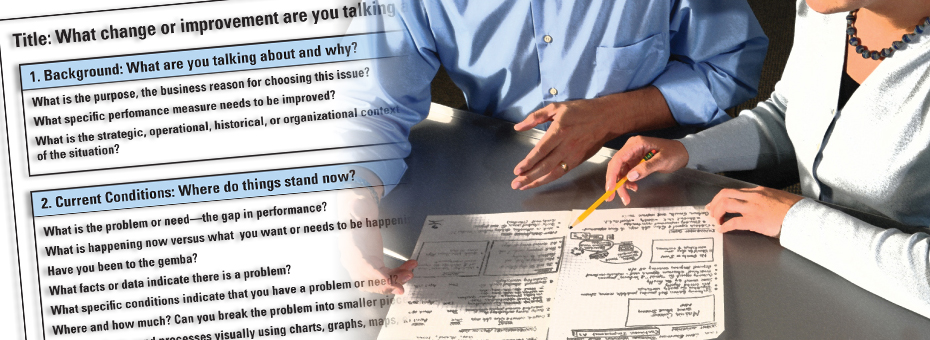

With the goal of “sharing wisdom” in mind, here is the way to “complete an A3.”

State Your Purpose

First, think about purpose. Your purpose is why you’re solving this problem. To do this effectively, identify the key performance indicator(s) (KPIs) you aim to improve with your problem-solving effort. Whether you want to address quality, safety, productivity, cost, or human resources, getting clear on purpose will ensure you are doing value-added work. As critical, stating your purpose in writing on the A3 enables you to share it with others, which will help you and others to establish a clear line of sight linking your problem-solving purpose with company goals.

Clarify Your Problem

Once you understand your purpose, take some time to clarify the problem by asking: What problem am I trying to solve? You may think you know, but more careful consideration usually reveals it to be something else. Also, share your A3 problem statement with others on your team to get their input.

A way to clarify the problem is by stating it as a gap between your current and ideal state. I suggest asking yourself two questions to understand this gap better:

- What is the current situation? (make it measurable by $, %, #)

- What is the ideal situation or the standard? (make it measurable by $, %, #)

The answers to these questions should, by default, reveal the gap or the quantifiable problem, also known as a “caused gap” problem, meaning you see a measurable difference between the current situation and the ideal or new standard situation. (A “created gap” would be more strategic, e.g., to create a lean culture throughout all functional areas of my organization.)

… not focusing on something you can measure will likely cause you to alleviate a symptom or place a band-aid on the problem, not solve it.

I often see people neglect measurability altogether at this caused-gap step, instead stating just an opinion or assumption they have about their current state: “This is the problem, and it happens due to X, Y, and Z reasons.” However, not focusing on something you can measure will likely cause you to alleviate a symptom or place a band-aid on the problem, not solve it.

Break Down Your Problem

Once your problem is clarified, break it down into manageable pieces. Many people try to tackle a huge or complex problem or too many problems in a single A3, but that’s not what A3 thinking is for and will only cause frustration. (For significant organizational problems, lean practitioners use the hoshin kanri process.) So upfront, you want to ask the 4 W’s: what, who, when, and where, which will help you narrow the scope of your problem and ensure you are only trying to solve one.

I like to use the analogy of a pie or pizza. If I try to eat the whole thing at once, I won’t feel great. The same goes for A3 thinking! If I try to solve a huge problem in one sitting, it will not end well.

Getting clear answers to the 4 W’s is similar to using a Pareto chart to help focus our attention on the most critical part of the bigger problem. We usually call this the “prioritized problem.” No one is saying the other pieces (problems) of the pizza aren’t important! We just need to eat one slice at a time. Think of it this way: you can’t map a process, find the point of occurrence of an error, or identify where a discrepancy is if you’re trying to do too many things at once.

Do Root-Cause Analysis

Once you identify the point of occurrences in the process, do root-cause analysis (through asking why) until you narrow down your problem to the two to three potential root causes. Remember: you are not trying to solve world hunger. Identify a manageable set of possible countermeasures. Be sure they are measurable. If, for example, my ideal state for processing insurance claims is ten days, and I currently process my claims in 20, I have a clearly defined gap: ten days. With each change to the process, I can track how much of the ten-day gap has been eliminated. Again, use very specific measures to track effectiveness.

Decide on a Countermeasure

Selecting the proper countermeasure is a crucial and challenging step. Many organizations, including Toyota, use a criteria (or evaluation) matrix to choose the most effective countermeasure. For example, you might consider such criteria as effectiveness, feasibility, cost, impact, and risk.

Once you select your countermeasure, involve all stakeholders in implementing it and track its effectiveness. Ask these primary process owners “why” things are happening at the gemba. If issues arise, resolve them by asking questions of yourself and your team members, which will help build everyone’s problem-solving capabilities. Also, if your countermeasure resolves the problem, it’s still important to track its effectiveness for some time to ensure sustainability. Once you confirm this, you can consider this countermeasure part of the work process, creating a new standard for it.

Identify Another Problem to Solve

Once you’ve successfully implemented a countermeasure to one problem and established a new standard, it’s time to move on to the next. Go back to the analysis step and select the next prioritized problem on the list. You want to continue to chip away at the gap, one measured problem at a time.

As you continue to use the disciplined thinking of the A3 process, you’ll quickly see that it’s so much more than a form to complete. Only a good thinking process (supported by doing) will give you a good A3 report, a document that helps you share your thinking and gain others’ input as you improve the work of the business. Soon enough, you’ll forget you ever felt eager to “fill in boxes.” Instead, you’ll find yourself taking your time, making sure the left side of your A3 is as accurate as possible — indeed, each step is as accurate as possible — before moving to the next.

As my trainers would remind me: executing a good A3 problem-solving process will give you the desired results, not the other way around. It’s not easy to do, but you must put process before results!

Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on March 12, 2014, one of the most popular posts about this vital lean practice.

Managing to Learn

An Introduction to A3 Leadership and Problem-Solving.