Years ago, when I worked in the tech sector, vendors that sold technology to major corporations equipped their salesforces with ROI calculators. These were essentially spreadsheets that collected numerical information from the customer and then computed the savings that could allegedly be realized from implementing the technology in question.

The purported benefits came in several categories—better quality, fewer mistakes, cost avoidance, revenue growth— but the only one that really held sway was the elimination of full-time employees (FTEs). Buy our software, the pitch went, and you can get rid of “X” many people.

The notion that an outsider can walk into a company, collect a few data points, and then use a generic calculator to generate a reliable prescription for replacing workers with technology is, of course, highly presumptuous and profoundly disrespectful of the people who do the work. Yet the federal government’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) appears to be doing precisely that.

DOGE recently fired tens of thousands of federal government employees with no more than a precursory AI-assisted determination that their work should be either eliminated entirely or automated by AI. DOGE hopes to fill the gap with the help of a generic ChatGPT-style AI tool, currently being tested in the Government Services Administration (GSA), called GSAi.

Aside from the fact that the entire government payroll consisted of only 4% of the federal budget, there appear to be no assurances that Americans will remain protected against natural disaster or foreign invasion, that Social Security checks will arrive on time, that bird flu won’t trigger another pandemic, that we won’t hit another plane on the runway, that we’ll have clean air and drinking water.

“Cuts can reduce expenses, but they can also reduce the value delivered to the American public,” wrote a federal government employee in a chat obtained by Wired magazine. “How is that captured in the scorecard?”

Cuts can reduce expenses, but they can also reduce the value delivered to the American public.

Few would dispute that there is waste in government. But without reference to a desired outcome, the word “efficiency” is meaningless.

What matters to tax paying citizens, and what the government should be pursuing, is the overall efficiency by which the government utilizes its resources in order to deliver each of its services. The word for that is productivity.

While productivity is recognized as perhaps the most important force for growing our economy, it is both difficult to measure and widely misunderstood. It is also sadly lacking in most organizations, public and private.

Productivity became a public issue in the U.S. during the 1970s. Japan had risen to economic stardom based on the achievements of Toyota and others that had doubled the productivity of their American rivals. In response, America’s low productivity became the subject of a 1981 Congressional investigation.

American companies reacted by adopting some valuable techniques that helped their production. What didn’t sink in, however, was that Japan’s productivity gains were largely due to a fundamentally different approach to management that emphasized respect for employees rather than seeing them as a cost to be reduced wherever possible.

Instead, most business leaders convinced themselves that technological superiority provided the most viable path. Thus, we saw GM’s disastrous attempt in the 1980s at a fully automated “factory of the future” and numerous failed office automation projects. The pattern became so prevalent that it was dubbed “Solow’s productivity paradox,” based on a comment by economist Robert Solow that “you can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics.”

Solow’s Paradox was confirmed by a 2013 Deloitte study on return on assets (ROA) for U.S. businesses, which showed that ROA declined steadily from 4.1% in 1965 to 0.9% in 2012.

These revelations didn’t get nearly the attention they deserved. Tech companies argued, and still argue today, that companies have been slow to adapt their business models to the digital age. Many companies sidestepped the issue by offshoring their productive work to regions where labor was cheap—a trend whose harm to the U.S. economy is only recently being fully acknowledged.

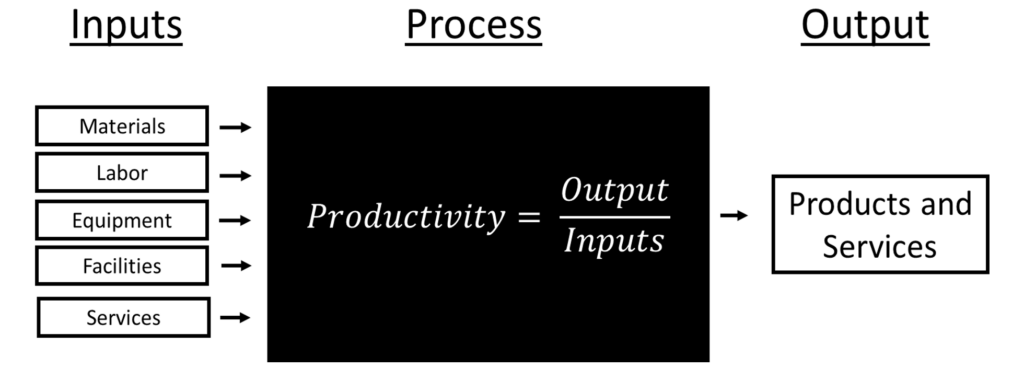

Politicians and economists have often pointed to a growing GDP as a sign that we must be doing something right. What they don’t mention is total factor productivity (TFP), also called multi-factor productivity, another metric tracked by the U.S. Government. TFP measures how efficiently an economy produces outputs in relation to all of the inputs, including materials, labor, equipment, facilities, and services. It is therefore the most comprehensive indicator of productivity, and the best indicator for understanding the productivity gap between the U.S. and Japan.

Between 1980 and 2023, TFP growth has averaged an unimpressive 0.8%, significantly lagging the 2.5% and 3%. GDP growth, despite significant investments in technology. In manufacturing, TFP has actually declined since 2010. Sadly, these numbers are all too indicative of an economy that is leaving so many people behind. They also show that the dire predictions of W. Edwards Deming and others regarding the ruin of U.S. industry have come to pass.

To understand how productivity eludes so many business leaders, we need to look at how it is reported in their companies’ financials.

Let’s start with the equation for TFP:

In most companies, decision makers get their productivity numbers from financial reports, which are treated as the definitive source of information about the business. All quantities are aggregated, typically in dollars. This means that total sales is the proxy for output, and inputs are represented by the aggregate quantities or costs of labor, materials, equipment, facilities, engineering, maintenance, etc. Many of these figures are derived from formulas and algorithms, some of which are highly questionable. An excellent analysis of this can be found in the 2003 book Real Numbers by Jean Cunningham and Orest Fiume.

Leaders who rely on these aggregated numbers remain uninformed about the thousands of incremental problems that exist in workplaces, and how work processes combine inputs to create value. Yet it is within the “black box” of process that game-changing productivity gains of Toyota and others have been achieved.

All the hallmarks of process improvement—shortening the timeline, eliminating the eight wastes, reducing defects, freeing up space, reducing WIP and inventory—are largely invisible in the financials. So is the magic of the Deming Chain Reaction by which quality and productivity improve together when process defects are removed.

This leaves leaders with a very limited productivity playbook—one that puts an outsized emphasis on cost-cutting but provides little guidance on how to improve value-add. Often, executives rely on industry benchmarks that purport to show what their costs or various ratios should look like. And headcount is invariably in the sight glass.

Conventionally managed companies do have operations departments, of course, and despite the process blindness of their superiors, many of them do excellent work. But when push comes to shove, it’s the financials that usually win out—a situation that is amplified in companies that prioritize quarterly results over all else.

Toyota’s approach to productivity is, of course, radically different. In addition to looking after the financials, senior management pays keen attention to non-financial indicators, particularly those that have to do with people. In his illuminating 2022 book Welcome Problems, Find Success, retired Toyota executive Kiyoshi Furuta sums it up:

“Toyota Japan used a single manufacturing KPI: Productivity. Other factors—such as quality, safety, and employee morale—were determined to be drivers that boosted labor productivity… This single KPI at Toyota Japan spurred amazing results: productivity increased 3–5% every year, every year for almost a half century [italics his], even during times of recession or when Toyota was relinquishing production volume to overseas plants. Productivity improvement was perfectly matched to the elimination of all waste—Toyota’s never-ending mission.”

While Toyota was never a laggard in adopting technology, it applied a measured approach rather than seeing technology as a magic bullet. As Furuta explains, strict return on assets (ROA) targets discouraged managers from overspending on technology in order to meet their productivity goals. Robots were therefore never adopted unless kaizens had failed to produce the desired improvements.

Lean icon Parker Hannifin provides an excellent example of this approach. “When automation is being discussed, we want to go in and take a look at the process and simplify that process as much as we can using our lean tools,” explains Stephen Moore, Parker-Hannifin Vice President, who has since retired. “That’s one of the first things we do when there’s a request to authorize the purchase of some capital equipment like a robot.”

Parker uses a hierarchical approach: first, simplify the process as much as possible; second, consider an unpowered mechanical solution, and only if that doesn’t work consider the programmed robotic option. Often, Moore explained, the resulting process simplification made automation unnecessary.

“We don’t want to automate waste,” says Moore. “If we do decide we need a robot, just like we would want to simplify an operator’s motions, we want to simplify the robot’s motions. Parts presentation and motion reduction are just as important to a robot as they are to a person.”

Automation also has high value, Moore notes, in eliminating manual tasks that are dull, hazardous, or physically stressful.

Some players in the tech world are coming on board with this approach. Collaborative robots or cobots, which are designed to share work with humans, are the fastest growing segment in robotics. For Denmark-based cobot vendor Universal Robots (UR), the business case for acquiring robots is not about reducing headcount but giving existing staff the tools to become more productive.

“Ten years ago, it was all about ‘if I put in a machine there, I can get rid of two people.’ That would then be your business case, and you wouldn’t be thinking much about anything else,” says Anders Billeso Beck, Vice President for strategy and innovation at UR. “Today, there’s a much bigger thought. You might say, ‘I’ve got two people, and I need to figure out, ‘How do I get all the production I need to run out of the machines I have on the shop floor?’ And those two people need to be able to operate the technology we bring in, to be able to set up the equipment and change batches. They need to be able to own that technology as part of their toolbox.’”

The key here is that automation is not being used to take over an entire process, but to be part of a solution that also includes people. If the practice of blending automation with human processes becomes the new reality, as some predict, the illusion that you can automate without understanding the process could become a thing of the past. And, not surprisingly, a number of tech companies are beginning to apply lean principles to their approach.

The key here is that automation is not being used to take over an entire process, but to be part of a solution that also includes people.

According to Dr. Alexander Wong, University of Waterloo engineering professor, Canada research chair in the area of artificial intelligence, and a founding member of the Waterloo Artificial Intelligence Institute, more businesses are beginning to see automation this way. “With robotics, most processes are not fully at the stage where we can fully automate them,” says Wong. “So this notion of collaboration with AI-equipped machinery is now a much more prevalent idea amongst the industries.”

A collaborative approach is also reflected in conceptual framework called Industry 5.0, which was adopted by the European Commission in 2021. Radically different from the technology-intensive Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0 outlines a human-centric approach to technology that seeks a balance between technology, people, and the planet.

None of this vision can be realized unless businesses gain a much deeper understanding of human productivity. In some cases, however, the establishment of collaborative automation involving people and technology is forcing the issue—these projects aren’t possible without understanding the process and fully engaging the people who live with it day-in and day-out.

In a March 18 speech at a tech forum in Washington D.C., Vice President J.D. Vance endorsed the idea of technology enhancing rather than replacing workers. “Real innovation makes us more productive,” he said, “but it also, I think, dignifies our workers. It boosts our standard of living. It strengthens our workforce and the relative value of its labor.”

Could developing events encourage DOGE to pivot to an approach based on engaging with workers and learning how technology could help them become more productive? Will successes with this new paradigm encourage more leaders to step away from their computers and discover how value is created in their organizations? And … will we finally start to make some real headway on the productivity crisis?

Time will tell!

Parts of this article were excerpted from Productivity Reimagined by Jacob Stoller, which was published by Wiley last October. For more information, please visit www.jacobstoller.com

The Management Brief is a weekly newsletter from the Lean Enterprise Institute that bridges the gap between theory and practice in lean management. Designed for leaders focused on long-term success, it delivers actionable insights, expert perspectives, and stories from real-world practitioners. Each edition explores the principles of lean management—strategy deployment (hoshin kanri), operational stability and continuous improvement (daily management), and problem-solving (A3)—while highlighting the critical role of leadership. Subscribe to join a growing community of leaders dedicated to creating organizations built for sustained excellence.

The Lean Management Program

Build the capability to lead and sustain Lean Enterprises